|

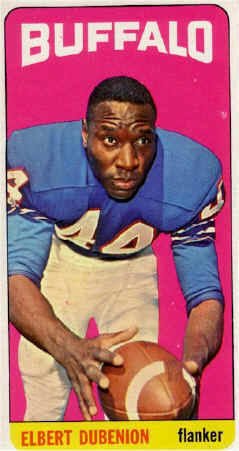

'Golden Wheels' used to

be Bills' touchdown man

By Erik Brady, The Buffalo News

Published 6:00 a.m. October 2, 2019

If you are a Buffalo Bills fan of a certain age, you

remember Elbert Dubenion as the fleet-of-feet flanker on the Bills’ AFL

title teams of the mid-1960s. Younger fans may know little more than

that his name is on the Bills Wall of Fame.

But know this: His nickname, Golden Wheels, is the best in Buffalo

sports history — and one of the best in all sports history.

This comes to mind because 10 days ago Dawson Knox bulldozed a couple of

Cincinnati Bengals and calls quickly rang out to find a fitting moniker

for the rookie tight end. One suggestion was Rambo, because he wore a

Rambo shirt after that game. Others included Hard Knox and Dawson’s

Freak.

But the one I like is Fort Knox. It conjures images of power and

stolidity, which is good, but harkens to the repository of the nation’s

gold reserves, which is better. That’s because Bills’ nicknames

referencing gold are, well, golden.

Dubenion’s sobriquet, as it happens, comes by way of a left-handed

compliment from a right-handed quarterback. Johnny Green was a backup QB

on the original Bills in 1960 who said of Dubenion: “Man can’t catch,

but he’s got those golden wheels.”

Green wasn’t wrong. Duby — that’s his more prosaic nickname — was a raw

talent with raw speed whose receiving skills were a work in progress.

Through hard work, his hard hands turned into soft ones, catching

hundreds of passes after practice, until he developed into an AFL

All-Star. And in 1964, when the Bills won their first AFL championship,

he had one of the greatest receiving seasons in pro football history.

Dubenion is 86 and now lives in a nursing home on the outskirts of

Columbus, roughly 90 miles from Bluffton, Ohio, where he played

small-college football. His daughter, Carolyn, says he was diagnosed

with Parkinson’s disease in 2007 and no longer is able to speak on the

phone.

But his career speaks volumes.

Duby caught 42 passes in 1964 for 1,139 yards. That’s an otherworldly

average of 27.1 yards per catch, the highest in pro football history

given a minimum of 40 catches. And yet, for all of that, his historical

import cannot be measured by mere numbers.

“He joined the team when the AFL was a shaky league struggling through

its infancy,” reads his bio on the website of the Greater Buffalo Sports

Hall of Fame. “Dubenion was the first great star” in franchise history.

“His exciting play helped the Bills and the AFL become viable.”

Sports Illustrated published a story in November 1962 on the viability

of the AFL when the upstart league was in its third season of

challenging the established NFL. That story includes a photo essay of

seven images of Dubenion returning a kickoff 100 yards for a touchdown

against the Boston Patriots.

“Buffalo is regarded as the best franchise in the AFL,” the SI story

said. “(AFL commissioner Joe) Foss once described it as ‘the pride of

the league,’ and TV broadcasters, using the hyperbole of their trade,

call it ‘the best city in pro football.’ However heady the praise,

Buffalo, hungry for pro football since the All-America Conference

collapsed in 1949, certainly has loyal fans.”

And Dubenion played a leading role in making that so. He was Jack Kemp’s

favorite target in the mid '60s glory years. And Daryle Lamonica liked

him too — Duby caught a 93-yard TD pass from Lamonica in a 1963 playoff

loss to the Patriots that will always stand as the longest postseason

pass in AFL history.

“Duby was our touchdown man,” says Booker Edgerson, a Bills cornerback

in those years. “They loved to throw him the bomb.”

Edgerson figures he became a better player for his years of playing

against Dubenion in practice. “He didn’t have those shake moves to get

open,” Edgerson says. “He could just flat outrun people.”

Carolyn Dubenion says her father often told a joke about that: “He

always said he ran so fast because he didn’t want to get hit.”

Dubenion was born in Griffin, Ga., and he was a small-college

All-America at Bluffton, a Mennonite university that counts Duby,

Phyllis Diller, the late comedian, and Hugh Downs, the late TV

journalist, among its greatest graduates.

Duby was drafted by the NFL’s Cleveland Browns in 1959 but an injury

kept him from trying out and he signed as a free agent with the Bills in

1960. In the first game in franchise history, a 27-3 loss at the New

York Titans, Dubenion dropped several passes and fumbled on a reverse;

he wondered if coach Buster Ramsey might release him.

But the next week, in the first home game in Bills history, Duby caught

TDs of 56 and 53 yards in a 27-21 loss to the Denver Broncos. And by

Week 4, Ramsey told reporters that Dubenion had developed beyond

expectations: “He was green as a gourd when he came to camp and he was a

disappointment in our first game in New York. But he didn’t quit on

himself and he improved 100%. Duby is now a pro.”

Dubenion retired in 1968 with 294 career receptions for 5,294 yards and

35 touchdowns as the last of the original Bills. He wouldn’t be gone for

long.

The next year, Duby returned as a scout. He stayed with the Bills

through 1978 and then, after two years scouting for the Miami Dolphins,

returned to Buffalo. Good thing, too, because he recommended that the

Bills draft a receiver from a lesser-known school in 1985.

“He always made a point of checking out the players from the small

schools,” Duby’s daughter says, “because he was from a small school,

too.”

Yes, the speedy receiver from Bluffton liked a shifty receiver from

Kutztown University — and in the fourth round, the Bills selected their

future Hall of Famer, Andre Reed.

Turns out Golden Wheels — a golden boy of the Bills’ golden years — had

a golden eye for talent. |